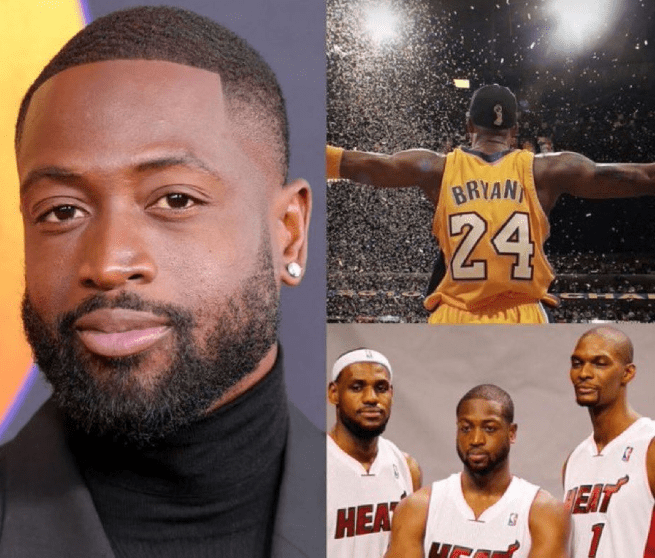

Dwyane Wade’s Shocking Confession: “I Failed LeBron James in the 2011 Finals”

Wade Takes Blame For LeBron’s Collapse:

The 2011 NBA Finals are the ghost that haunts LeBron James’s otherwise untouchable legacy. It is the glaring blemish, the inexplicable collapse, the series that for years was explained with one simple narrative: LeBron choked. The story was written, the history books recorded it, and fans and critics alike pointed to his 17.8 points per game and hesitant play as the sole reason the superstar laden Miami Heat fell to Dirk Nowitzki’s Dallas Mavericks. But history, like memory, is often incomplete. Fourteen years later, a key architect of that team has stepped forward to rewrite the story from the inside.

In a raw and revealing interview, Dwyane Wade did not defend his former teammate; he indicted himself. His confession is not a footnote; it is an earthquake that forces us to re examine everything we thought we knew about one of sports’ greatest failures. Wade didn’t just say they lost. He said, “We got outplayed, and we got outcoached. Me as a leader. Spo as a head coach. We have to do better to make sure he’s not struggling.” And with that, the burden of 2011, carried for so long by LeBron James alone, has been permanently, irrevocably shared.

To understand the weight of Wade’s admission, you must first understand the absolute frenzy surrounding the 2011 Miami Heat. This was not just another superteam. This was a cultural phenomenon born from “The Decision,” a televised spectacle that made LeBron James the most famous and most villainous athlete on the planet. He wasn’t just joining Dwyane Wade and Chris Bosh; he was fleeing Cleveland for a ready made contender in South Beach, promising not one, not two, not three… but multiple championships. The pressure was cosmic.

Every game was a national event, every loss a referendum on their arrogance. They were the heroes in Miami and the villains everywhere else, a dynamic that weighed heaviest on LeBron, the man who had chosen to be the face of it all. When they marched to the Finals in their first year together, it felt like destiny. Facing the aging Mavericks, they were overwhelming favorites. The story was supposed to end with a coronation. Instead, it became a funeral for their invincibility. LeBron’s stats tell the tale of an individual failure: a passive, uncharacteristically inefficient series where he seemed to shrink from the moment. But Wade’s confession suggests those stats were merely a symptom.

Dwyane Wade was not a bystander in 2011; he was the incumbent king of Miami. Before LeBron’s arrival, this was Wade’s city, Wade’s team, fresh off a 2006 Finals MVP performance. His willingness to recruit LeBron and Bosh was celebrated as the ultimate sacrifice. But sacrifice on paper is different from sacrifice in practice. As the season unfolded, an unspoken tension simmered: Whose team was this really? Wade, by his own new admission, saw himself as the leader.

He was the one who knew the culture, the franchise, the coach. He had the ring. In the pivotal moments of that Finals, this dynamic played out in devastating clarity. Wade recalled the now infamous clip where he is seen on the bench, face contorted, cursing into LeBron’s ear during a timeout. “That’s probably not the way I should’ve done it,” he now concedes. In that moment, the leadership model was revealed. It wasn’t a collaborative effort to solve a problem; it was a star publicly chastising his struggling co star. Instead of a arm around the shoulder, LeBron got a finger in his face.

This was Wade’s “leadership” in its rawest form, and he now recognizes it as a catastrophic error. He was trying to provoke LeBron by challenging him, but the effect was the opposite. It reinforced a hierarchy, highlighted the pressure, and likely deepened the mental block LeBron was experiencing. Wade was treating LeBron like a subordinate who needed to be yelled into greatness, not a partner who needed to be elevated.

If Wade failed as the team leader, Erik Spoelstra now revered as a coaching genius failed as the architect. Spoelstra was a young coach, elevated from within the Heat system, suddenly tasked with managing three colossal egos and the brightest spotlight in sports. His challenge was monumental: devise an offensive and defensive system that maximized three ball dominant stars, establish a clear pecking order, and manage their minutes and moods. According to Wade’s new framework, Spoelstra did not succeed in 2011. “We got outcoached,” Wade states plainly.

The tactical brilliance of Mavericks coach Rick Carlisle, who deployed a zone defense that confused the Heat and expertly targeted defensive mismatches, is well-documented. But Wade’s criticism seems to go beyond Xs and Os. It points to Spoelstra’s failure to establish the psychological and strategic framework that would have allowed LeBron to thrive. The offense often devolved into stagnant isolation plays, with Wade and James taking turns rather than playing a synergistic, fluid style. There was no clear, consistent plan for how to use LeBron, especially in crunch time.

Was he the primary scorer? The playmaker? The decoy? The confusion was palpable. Spoelstra, still finding his voice against the megawatt personalities of his stars, could not impose the structure they desperately needed. He was outmaneuvered by Carlisle and, by Wade’s assessment, failed to put his best player in a position to succeed mentally or physically. The coach’s growth in the subsequent years, leading to two championships, is a testament to his ability, but it also highlights how raw and unresolved the coaching dynamic was in that first, fateful season.

The psychological toll on LeBron James during the 2011 Finals cannot be overstated, and Wade’s comments finally provide the context for it. LeBron has since said that in Miami, he was trying to “prove everybody wrong” and that he “literally lost myself.” He concluded, “We lost because I wasn’t even there.” This is a description of a profound mental disconnect, a form of athletic dissociation. He was paralyzed by the fear of failure, the hatred from opposing crowds, the weight of his own decision, and the expectation of immediate perfection.

Into this psychological vortex stepped not a supportive structure, but a compounding pressure system. Wade’s confrontational leadership and Spoelstra’s uncertain schemes did nothing to alleviate this pressure; they amplified it. LeBron was not just fighting the Mavericks’ defense; he was fighting his own mind, his new teammate’s expectations, and a coaching plan that seemed to have no answers. When he passed up open shots or made uncharacteristic turnovers, it wasn’t merely a skill failure.

It was the external manifestation of an internal crisis. He was a Ferrari being driven by a committee who couldn’t agree on the map, while one of the other drivers kept yelling about his shifting. Wade’s admission validates this view. He is essentially saying the team’s leadership did not create a safe, structured, and supportive environment for LeBron to work through his struggle. They left him to drown in it.

Chris Bosh, the oft-forgotten third member of the Big Three, played a unique role in this drama. Bosh had willingly taken the largest step back, morphing from a 24 points per game star in Toronto into a floor-spacing big man who often took the third most shots. His sacrifice was clear and necessary. However, in the 2011 Finals, Bosh was arguably the Heat’s second-best player, averaging 18.5 points and 7.3 rebounds.

Yet, his success did little to alleviate the central tension between Wade and James. If anything, it highlighted the awkward fit. The offense never fully optimized how to use all three together. Bosh’s adaptation was personal, not systemic. The team’s failure to develop a true three star ecosystem meant that when LeBron faltered, there was no seamless, organic way for Bosh to step into a larger offensive role without it feeling like an ad-hoc deviation. He was a luxury item the Heat hadn’t learned to fully integrate, and thus, he couldn’t become the stabilizing force that might have steadied the ship when the two alphas struggled with their dynamic.

The Dallas Mavericks, led by the legendary Dirk Nowitzki, were the perfect storm to exploit every single one of Miami’s fissures. They were not more talented, but they were, as Wade admits, “a better team.” They had a clear, unquestioned leader in Dirk, who played through illness and injury with a legendary performance. They had a veteran roster of players like Jason Kidd, Jason Terry, and Shawn Marion, who knew their roles perfectly. Most importantly, they had Rick Carlisle, a coach who masterfully out-schemed Spoelstra. Carlisle’s use of a zone defense baffled the Heat’s iso-heavy attack.

He expertly hunted mismatches on defense, and his team executed with a cold, collective purpose. The Mavericks saw the tension in the Heat and poured salt in the wound. They played with a chip on their shoulder, a collective desire to humble the arrogant superteam. Every missed Heat shot, every frustrated interaction between Wade and James, fueled them. They were the living embodiment of team basketball triumphing over a collection of individuals, and they exposed the Heat’s dysfunctional foundation for the entire world to see.

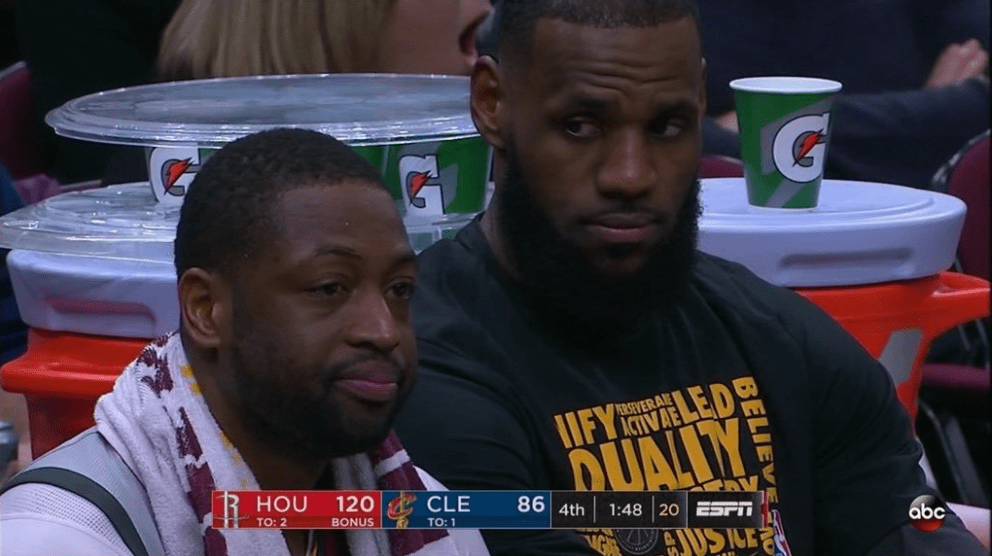

The immediate aftermath of the loss was brutal. LeBron James became a global punchline. “The Decision” was framed as a monumental failure. Critics said he couldn’t win the big one, that he lacked the “clutch gene.” The narrative was set in stone: LeBron choked. Within the Heat, however, the loss forced a painful but necessary reckoning. Wade’s confession indicates that this reckoning began with self reflection, at least for him. It is widely reported that after the Finals, Wade, James, and Spoelstra had to engage in difficult conversations.

Wade had to cede control and truly embrace LeBron as the team’s best player and primary offensive engine. Spoelstra had to grow into a stronger, more authoritative voice. LeBron had to return to his roots, working with Hakeem Olajuwon to develop his post game and recommitting to a more aggressive, assertive style. The result was a metamorphosis. The Heat returned in the 2012 season with a clearer identity. LeBron was the unquestioned MVP and leader. Wade gracefully accepted a secondary, off-ball role that showcased his cutting and intelligence. Spoelstra implemented a more dynamic, positionless system.

They faced even greater pressure in the 2012 Finals against Oklahoma City, but this time, the leadership and structure held. LeBron delivered a legendary performance to win his first championship, a direct product of the lessons seared into them by the 2011 failure.

Wade’s decision to publicly shoulder this blame now, over a decade later, is profoundly significant. It is an act of historical honesty and personal accountability rare among sports legends. It does not erase LeBron’s poor play, but it recontextualizes it. It shifts the 2011 narrative from a simple tale of individual failure to a complex case study in team building, leadership, and psychology.

It shows that even the most talented assemblages can fail if the human elements trust, role clarity, support are neglected. For LeBron’s legacy, this is a form of absolution. The biggest stain on his career is now understood not as a pure personal shortcoming, but as a collective breakdown where the support system around him failed. It completes the story that LeBron himself started when he said he “wasn’t even there.” Now we know why he felt so lost.

Ultimately, Dwyane Wade’s confession is more than just about basketball. It is a lesson in leadership that extends far beyond the court. True leadership is not about being the loudest voice or the top scorer. It is about perception, empathy, and creating an environment where everyone, especially your most important asset, can succeed. In 2011, Wade led with his emotions and his ego. He now realizes that in the most critical moment, the best way to lead LeBron James was not to curse at him, but to lift him up. That failure cost the Miami Heat a championship and defined a legacy. By finally admitting it, Dwyane Wade has not only rewritten history but has provided the ultimate lesson: the hardest thing to lead is not a team, but yourself.