From $21 Million to Eviction: The Catastrophic Unraveling of Latrell Sprewell, The NBA Superstar Who Choked His Future Along With His Coach and Learned That Pride Is the Most Expensive Luxury Item of All

The image is one of the most jarring in sports history: not of athletic triumph, but of financial surrender. In the summer of 2007, a federal marshal seized a 70-foot Italian luxury yacht named “Milwaukee’s Best” from a storage facility in Manitowoc, Wisconsin. Its owner, Latrell Sprewell, was not present. The four-time NBA All-Star, once one of the league’s most ferocious and explosive scorers, was elsewhere, likely dodging a different kind of pressure the relentless, unyielding crush of creditors.

This was not a strategic sacrifice. It was a repossession. The boat, a $1.5 million floating trophy purchased at the height of his fame, was sold at auction for $856,000, leaving Sprewell still owing nearly half a million dollars on its mortgage. The seizure of the yacht was not the end of his financial catastrophe; it was the most vivid public symptom of a systemic collapse already in progress. Just months later, the bank would initiate foreclosure on his River Hills mansion for missed mortgage payments.

The state of Wisconsin would eventually name him its top tax delinquent, owing over $3 million in back taxes. This is the story of a stunning, self-inflicted economic implosion that stands as one of professional sports’ most potent cautionary tales. It is a narrative that begins with an unfathomable act of pride the rejection of a $21 million contract extension with the infamous declaration, “I’ve got my family to feed” and ends with a former millionaire renting a modest bungalow and facing noise violation tickets.

Sprewell’s journey is not merely about money lost; it is about a complete psychological rupture from reality. It exposes the lethal cocktail of unchecked ego, catastrophic financial advice, and a fundamental misunderstanding that an NBA career is not an endless well of wealth, but a fleeting geyser that must be harnessed before it runs dry. He mistook a paycheck for a birthright, and in doing so, engineered his own demise not on the court, but in the courtrooms and bank ledgers that would eventually strip him of every tangible symbol of his success.

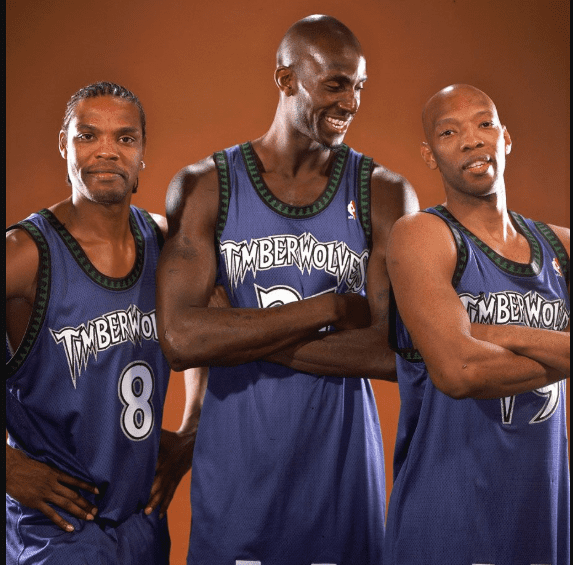

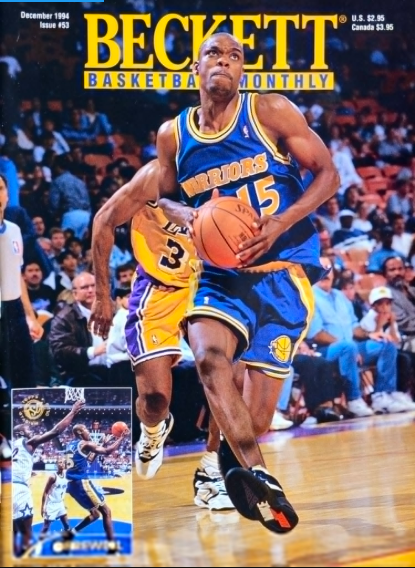

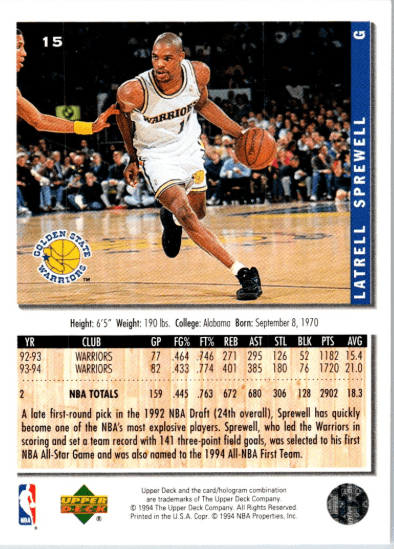

To understand the sheer scale of Sprewell’s financial freefall, one must first appreciate the peak from which he jumped. In his final NBA season with the Minnesota Timberwolves in 2004-05, he was earning $14.6 million per year a salary that placed him among the top ten highest-paid players in the entire league. As that contract neared its end, the Timberwolves, hoping to retain a key piece of their veteran core, offered him a three-year, $21 million extension. In the cold math of aging athletes, it was a generous offer for a 34-year-old whose production had already begun to decline. Sprewell’s rejection was not just a negotiation tactic; it was a philosophical statement of perceived self-worth.

He infamously told the St. Paul Pioneer Press, “Why would I want to help them win a title? They’re not doing anything for me. I’ve got a lot at risk here. I’ve got my family to feed”. The quote instantly entered the sports lexicon as a symbol of athlete avarice, a disconnect so profound it seemed parody. But for Sprewell, it was a deadly serious miscalculation. His agent, Bob Gist, reportedly advised holding out for a better deal, even stating Sprewell would not “stoop or kneel” to accept a team’s $5 million mid-level exception.

This strategy presumed a demand that did not exist. No other team offered him a contract. The 2005 offseason passed. The 2006 season began. Latrell Sprewell, at age 35, was suddenly and permanently out of the NBA. The $21 million safety net he had spurned was gone. The $14.6 million annual geyser had stopped. And the bills on a lifestyle built for a king were just beginning to come due.

The Anatomy of a Collapse: How the Debts Stacked Faster Than Points

Sprewell’s financial ruin was not caused by a single mistake, but by a cascade of fixed, extravagant liabilities that continued to demand payment long after his income stream vanished.

The most symbolic was the yacht, “Milwaukee’s Best.” Purchased in 2003 for $1.5 million through his company LSF Marine Holdings, it came with a brutal monthly mortgage payment of $10,322. This was not a one-off purchase; it was a perpetual financial anchor. When Sprewell stopped making payments and failed to maintain insurance, North Fork Bank moved swiftly. The auction sale for $856,000 in 2007 failed to cover the $1.3 million debt, leaving a $500,000 shortfall haunting him.

Simultaneously, his primary residence a home in the affluent Milwaukee suburb of River Hills purchased in 1994was also in jeopardy. He had stopped making the $2,593 monthly mortgage payments in September 2007. By early 2008, the bank had filed for foreclosure, citing $295,138 in outstanding payments plus interest. While he eventually settled this debt for roughly $320,000 to avoid a sheriff’s sale, it was a temporary reprieve in a losing war.

Beneath these visible debts festered a far more insidious liability: tax evasion. According to a 2013 report, court records showed Sprewell owed the state of Wisconsin more than $3 million in back taxes, earning him the state’s top spot on its list of tax delinquents. This wasn’t an oversight; it was a massive, compounding debt with penalties and interest that would cripple any financial recovery.

This trifecta luxury asset debt, real estate debt, and government debt formed an inescapable trap. Each required five-figure monthly outlays he could no longer afford. The math was simple and brutal: Zero income cannot service millions in fixed expenses. His wealth didn’t evaporate; it was systematically repossessed and claimed by entities with far more power than any NBA defender.

The Psychology of the Fall: Pride, Entitlement, and a Fatal Misreading of the Market

The financial mechanics of Sprewell’s collapse are straightforward. The psychological drivers are far more complex and revealing of a mindset that plagues many star athletes.

At its core was a profound entitlement. Sprewell’s “family to feed” comment was not about literal starvation; it was a metaphor for maintaining a lifestyle he believed he was owed in perpetuity. He viewed the $21 million offer not as future earnings, but as an insult to his past contributions. This mentality blinded him to the cold reality of professional sports: your value is what the market will pay today, not what you were worth yesterday.

This was compounded by what appears to be catastrophically bad counsel. His agent’s strategy to wait out the market until teams became “desperate” was a gross misreading of the NBA’s collective bargaining landscape and Sprewell’s own depreciating value. The advice transformed a negotiation into a career-ending standoff.

Sprewell also exhibited a classic symptom of financial dissociation. He spent as if his peak earning years were a permanent state, not a temporary peak. The yacht, the mansion, the lifestyle all were funded on the assumption that the $14.6 million annual income was a floor, not a ceiling. He failed to differentiate between wealth and cash flow. He had massive expenses but no plan to create passive income or capital reserves once the active NBA checks stopped.

This psychology created a reality distortion field. Even as banks seized his assets and the state pursued him for millions, his public persona suggested a man in denial. Years later, in 2013, he was cited for noise violations at a rented bungalow in Milwaukee, a stark contrast to the quiet luxury of his foreclosed River Hills estate. The fall was not just financial; it was a complete departure from the world he once inhabited.

The Wider Context: Sprewell as the Ultimate Cautionary Tale in a League of Burnouts

Latrell Sprewell’s story is extreme, but it is not unique. It exists on the far end of a spectrum of professional athletes who earn life-altering money and end up bankrupt. He embodies every classic pitfall.

He is the avatar of “Lifestyle Inflation” gone malignant. His fixed costs (yacht payment, mansion mortgage, tax bills) rose to meet and then exceed his astronomical income. When the income vanished, the costs remained, acting like financial vampires.

He exemplifies the “Yes Men” syndrome. The lack of any visible, forceful financial advisor to counter his and his agent’s hubris is glaring. There was no one in his circle willing to say, “This is a good offer. Take it, secure your family, and then manage your spending.” Instead, he was surrounded by enablers who validated his inflated self-worth.

His case also highlights the danger of conflating brand with skill. Sprewell was a famous, controversial star (“Spree”). He may have believed his notoriety had its own monetary value that would translate to post-career opportunities or leverage. It did not. The NBA only pays for current basketball utility. His brand, built on defiance, had no financial utility to other teams once his skills diminished.

Finally, his tax debt reveals a particularly disastrous form of magical thinking. Ignoring multi-million-dollar tax obligations isn’t a strategy; it’s a fantasy that the rules don’t apply. The government, unlike a bank, has nearly unlimited power to collect. This debt alone would have doomed any chance of a stable financial future.

The Aftermath: From Foreclosed Mansions to a Rented Bungalow

The final stage of Sprewell’s financial journey is a portrait of staggering diminishment. The man who once owned a yacht and a mansion in River Hills was, by 2013, renting a 2,044-square-foot bungalow on Milwaukee’s East Side.

The house, valued at around $307,100, was a fraction of his former holdings. He was not an owner but a tenant, subject to a landlord and local noise ordinances one of which he violated, leading to a citation on New Year’s Day 2013. The report also noted he had whittled his massive state tax debt down from over $3 million to $110,000, a Herculean effort that still represented a monumental burden.

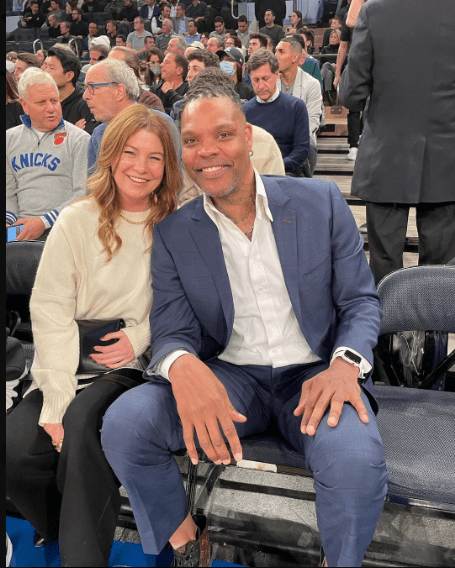

In a minor redemption arc, later reports indicate Sprewell eventually found work in community relations with the New York Knicks and as a media personality for Madison Square Garden, leveraging the one asset he never lost: his name and his history with a iconic franchise. His estimated net worth was listed at $150,000 a sum he once might have spent on a single piece of jewelry.

The Unseen Victims: The “Family to Feed” in a Financial Famine

The cruelest irony of Sprewell’s saga is the fate of the very family he claimed he was protecting with his contract stance.

When he declared he needed to “feed his family,” he framed himself as a provider. His subsequent financial collapse exposed that declaration as a hollow slogan. True provision involves long-term security, education funds, and generational planning not monthly yacht payments.

The foreclosure on the family home and the seizure of assets represented a profound failure of this duty. The stability he promised was replaced with legal chaos, public humiliation, and a drastic downgrade in living standards. The “family” was not fed; it was exposed to the trauma of financial instability and the loss of their home.

This aspect transforms Sprewell’s story from a personal tragedy to a moral failing. His pride and poor decisions did not just affect him; they pulled his dependents into the vortex of his downfall. The banks and the state were not the only creditors; his family was owed a responsible stewardship of the fortune he earned, and that debt went tragically unpaid.

The Verdict: A Self-Made Tragedy With a Permanent Legacy

Latrell Sprewell’s story is not one of bad luck or market forces. It is a textbook case of self-sabotage. He was not a victim of circumstance; he was the architect of his own ruin.

The verdict is clear: he overvalued himself, undervalued security, and ignored every principle of wealth management. He turned down generational wealth for the fleeting satisfaction of perceived respect. He chose monthly liabilities over long-term assets. He ignored the tax man until the tax man owned him.

His legacy in basketball is dual: a fierce, captivating competitor who helped lead the Knicks to the NBA Finals, and the man who choked his coach. His legacy in finance is singular: the ultimate “What Not To Do” case study.